Guest Blog

Running the MCAT Race

Kelan Queenan

Palms sweaty. Heart racing. Stomach churning. It’s 6am on a Friday. The sun has yet to rise and lines are already forming outside. Competitors are in the midst of warming up. My Airpods are blasting “I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor. The finish line is so close! I have trained months for this race and am about to put my hard work to the ultimate test… At last, I sit down for the Medical College Admissions Test, the MCAT.

While the MCAT may not be as fun as running a half-marathon, there are many parallels when preparing for both challenges. As a half-marathon training plan might consist of fartlek, tempo, and long runs, an MCAT studying plan may include practice exams, content review, videos, and flashcards. Both prove to be true endurance tests summoning even the most skilled athletes and scholars.

Experts agree that the weeks leading up to a race are critical. In the final weeks, runners will taper their workouts, gradually decreasing their mileage. I believe the same approach is beneficial when studying for the MCAT. Rather than cramming in problem sets, I think students should actually decrease the amount of studying they do the last few weeks, allowing their minds to clear and their focus to sharpen.

Familiarize yourself with the course. Is the race route hilly? Will there be traffic on the way? Practice driving to the test site on the same day of the week, at the same time, just like you would on test day. Some students let MCAT studying completely consume them, sacrificing their physical, mental, and social health. It's crucial to maintain your exercise routine, nutrition, and hydration leading up to the test. When taking practice exams, I did my best to mimic race conditions -- waking up at the same time, eating the same breakfast, wearing the same outfit, and even setting my driver’s license on the desk as I would when taking the MCAT.

Race day is here. You’ve trained months for this. Meditate. Focus. Execute. Whether you are running a half-marathon or taking the MCAT, just remember what Gloria Gaynor said: YOU WILL SURVIVE!!!

From Running for Survival to Running Marathons: How Our Feet Feel the Impact.

Caroline Rush

Modern running practices could be considered a whole new sport compared to the primitive days of running. In the story of evolution, humans started to run for survival, escaping attacking animals and tiring prey. Through natural selection human anatomy evolved to allow us to run distances better than most animals, with more efficient cooling and breathing mechanisms as well as our bipedal stride. Distance is where humans have always had an advantage. However, if distance running is a key element to early human survival, why is it now fairly rare and often accompanied by injuries?

Modern running injuries can be attributed to a variety of factors. However, in terms of evolution, popular opinion accredits these sport-related afflictions to the manner in which the human gait has developed over the past few centuries. In the days of running to tire our prey, humans wore minimal, if any footwear. Currently, the global athletic footwear market is a hundred-billion-dollar industry and runners are presented with thousands of sneaker options, complete with fiber plates and 10-millimeter heel drops. With more cushion in our sneakers now, we can comfortably land without our bodyweight exerting a massive force through our heel. This is in stark contrast to the days of running barefoot or in thin sandals, which cannot quiet the force of a heel strike.

When we run barefoot, the instant feedback from the ground urges us to run with a gentler foot strike, but modern cloud-like sneakers don’t require this diligent technique. The common gait in contemporary runners lead with the heel of the foot, referred to as a rearfoot strike. This places the runner in the braking phase of their gait with the swinging leg stretched in front of them, requiring extra energy to overcome the breaking phase and propel forward. Landing closer to the ball of our feet rather than the heel is referred to as a forefoot strike, which places the foot closer to the runner’s center of gravity upon hitting the ground, maintains propulsion, minimizes impact force, and maximizes spring force. When running without cushioned shoes, this forefoot running technique is much less painful than rearfoot strides and is what the human running gait looked like early in our evolution.

Although many factors lend to modern running injuries, mismatch between how our running technique evolved and how we run today is certainly important to consider. Forefoot strike running reduces stress on the hip and knee joints but can also increase stress on the ankle joint (Xu et al., 2021). An interesting study by Diebal et al. in 2012 showed that switching technique to a forefoot strike from a rearfoot strike may be beneficial to runners who experience exercise-induced compartment syndrome by reducing the stress on the anterior compartment of the leg.

Evidence for switching from a rearfoot to a forefoot strike technique to prevent injury is inconclusive but provides an interesting insight into the ways our body has adapted to the commodification of running. Our gait mechanics have completely changed as a result of technology facilitating massive amounts of force through our heel. With the current trend of increasing cushion, there may come a day that research suggests decreasing the level of padding for the sake of our hips and knees.

Sources:

- Diebal AR, Gregory R, Alitz C, Gerber JP. Forefoot running improves pain and disability associated with chronic exertional compartment syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1060-1067.

- Xu Y, Yuan P, Wang R, Wang D, Liu J, Zhou H. Effects of Foot Strike Techniques on Running Biomechanics: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Health. 2021;13(1):71-77.

The cold, hard truth about ice…Olivia Gordon

Remember in elementary school when you bumped your head or twisted your ankle at recess, the school nurse always gave you ice? No matter the injury, a cold pack was usually the answer. The application of ice—both as a pain modulator and as a method of reducing swelling—has been common practice throughout the entire medical field for years.

In the same vein, if you’ve ever been injured, I’m sure you’ve heard the term "RICE." RICE is an acronym coined by Dr. Gabe Mirkin in "The Sportsmedicine Book (1978)", which stands for Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation. Previously, RICE served as the standard protocol for the treatment of acute sports injuries, hence, why you always received an ice pack from the school nurse. Nevertheless, the RICE protocol has since been called into question.

When you experience an injury, your body’s tissues, such as muscles, ligaments, and/or tendons, become compromised. The human body responds by initiating a cycle that includes three phases that are critical to the healing process: 1) inflammation, 2) repair, and 3) remodeling. Each of these phases is a catalyst for the next to commence.

During the initial phase of this cycle, the immune system sets recovery in motion by sending out first responders, such as inflammatory cells, to the tissue or tissues that have been damaged. These cells are carried to the site of injury via the bloodstream. Ice interferes with this process, decreasing inflammation as it acts as a vasoconstrictor. Per their name, vasoconstrictors cause the muscles surrounding your blood vessels to tighten. The contraction of these muscles restricts the flow of blood, slowing and inhibiting inflammatory cells from reaching the site of injury, and ultimately reducing swelling.

While it’s true that minimizing inflammation are critical parts of injury recovery, it’s also important to remember that inflammation as a response to an injury allows your body to recognize that its tissues require repair. In other words, it is vital for inflammation to occur so the immune system can initiate the remodeling of damaged tissues. Along with inflammatory cells, the process of inflammation also brings fluid, certain immune cells including neutrophils and monocytes, proteins, and antibodies to the site of injury. These materials contain healing properties that help the body fight off foreign organisms it may have been exposed to during injury, for instance, through an open wound.

Given this, despite past common practice, ice—and, more broadly speaking, the RICE protocol—are no longer the first line of defense in treating acute injuries as it disrupts the body’s natural mechanism of initiating healing. Now, some recommend MEAT instead. MEAT stands for gentle Movement, the re-establishment of and/or return to a regular Exercise routine, the use of Analgesics for pain control/management, and individualized Treatment that is conducive to long-term healing, such as a course of physical therapy, kinesiology taping, acupuncture, and/or supplemental/nutritional intervention.

References:

- https://thesportjournal.org/article/the-r-i-c-e-protocol-is-a-myth-a-review-and-recommendations/

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/21697-vasoconstriction

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/21660-inflammation

- https://recoupfitness.com/blogs/news/the-truth-about-inflammation-and-injury-recovery

- https://motusspt.com/meat-vs-rice/

- https://thesportjournal.org/article/the-r-i-c-e-protocol-is-a-myth-a-review-and-recommendations/

Pickleball Shoulder: Don’t Get Caught in a Pickle Abigail Smith and Elizbeth Matzkin, MD

Let me introduce you to the fastest growing sport in the U.S.: pickleball!

This game is taking the sporting world by storm with new players, young and old, jumping on the wave. According to USA Pickleball, the best way to describe the sport is a combination of tennis, badminton, and ping-pong. It can be played indoor or outdoors, and only requires a small amount of space. It can be played as doubles or singles and is accommodating of all skill levels. With an increase in pickleball popularity, also comes an increase in pickleball injuries.

Without the proper warm up or form, injuries can happen in pickleball just like in any other sport. Data collected from 2010-2019 from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System showed an increase in the rate of pickleball injuries, both upper and lower body, over this time period. It was found that 85% of the injuries occurred in players aged 60 and up.

Shoulder injuries are often associated with over-head sports such as tennis, golf, volleyball, etc., and now pickleball. Common shoulder injuries include bursitis, tendonitis, and rotator cuff tears. During swinging motions stress can be applied to the shoulder joint. Impingement occurs when the humerus and rotator cuff tendons rub against the acromion bone during outwards motions. This could be during pickleball serves or strokes. This impingement can cause the cuff or bursae to become irritated and cause pain. With significant amounts of overuse and/or weak rotator cuff muscles, tears can happen.

There are many different treatment options for pickleball shoulder pain ranging from physical therapy, injections, or surgery in extreme cases. Luckily, many of these shoulder injuries can be mitigated by creating a proper warmup and recovery routines for before and after pickleball. To reduce the onset of pickleball shoulder pain:

- Warmup your shoulder and rotator cuff before playing.

- Use proper equipment (racquet size and grip)

- Practice good form and mechanics

- Stretch after playing

- Take time to recover: rest, ice, take anti-inflammatory, etc.

- Rotator cuff strengthening exercises to keep you in shape to keep playing

Even though playing a match with your friends on a Sunday seems low stakes, it still is a sport that requires fast, reactive moments, as well as upper and lower body mobility and power. Don't get caught in a pickle and let shoulder pain or injury keep you from playing.

Sources used:

https://usapickleball.org/what-is-pickleball/

https://injepijournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40621-021-00327-9

https://floridaspineandsportsspecialists.com/shoulder-pain-impingement-in-pickleball/

https://www.forbes.com/health/body/what-is-pickleball/(image)

"There’s No Whining in Ski Racing:" Psychological Expectations in Alpine Ski Racing and Gender Differences in Recovery Post ACL Injury

By Olivia Jochl

I grew up ski racing in a family of ski racers. My dad raced for Austria in his youth, and my mom competed with the U.S. Ski team for years. Like most sports, ski racing is tough. In addition to the obvious physical demands, skiing required psychological discipline. You can get hurt fast if you doubt yourself for a split second while flying down the mountain. Meanwhile, the competition in individualized sports can easily get in your head. Just look at Mikaela Shiffrin, the world’s best skier, and her struggle to finish even one race at the last Olympics.

When I was a kid, my dad always told me, "there’s no whining in ski racing." Mental toughness, like with many sports, makes up a large part of the ski racing battle. Of course, pain and injury warranted emotion, but quick mental recovery was an expectation. During my time at Stratton Mountain School, a small winter sports academy, many kids suffered intense physical injuries on the mountain. In a two-year span, I suffered two anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, and I remember at least three of my female teammates tearing at least one in the same period. It was common for us. Occasionally, a men’s team member joined us to rehab after their ACL tear, but often, it was just us girls. While we worked hard to regain strength and our trainers and coaches supported us constantly, we rarely talked about the emotional toll these injuries took on us. As I said, there’s no whining in ski racing.

My small ski team mirrored the research findings suggesting female athletes experience knee injuries at higher rates than males, especially of the ACL, and find less success returning to their sports. Compared to males, females are 1.4 times less likely to return to their pre-injury level of competition after ACL reconstruction. Meanwhile, approximately 27% of young female athletes who returned to their sport suffered a second ACL injury within two years of surgical reconstruction.

Many hypotheses based on the biological variations between males and females attempt to explain the cause of the discrepancies in injury and reinjury rates. For example, researchers have proposed that differences such as hormones, strength, and q-angle, the angle at which the femur meets the tibia, produce more ACL injuries in females. However, none of these proposals have been convincingly proven by rigorous scientific studies, and the reasons for higher rates of ACL reinjury in females remain poorly understood.

Recent exploration into the psychological differences between males and females during the post-operative surgical rehabilitation phase reveals how gender-specific psychological interventions could impact recovery and return to sport after ACL reconstruction. A 2020 study reported that high school-age athletes with ACL tears described different psychological factors related to return to sport, locus of control, and psychological distress. Researchers noted that males felt frustrated with physical limitations after ACL reconstruction but described greater self-efficacy associated with a positive mindset. Meanwhile, according to their data, females experienced periodic psychological distress changes due to daily progress's ups and downs and felt motivated by social support. Both sexes reported fear of reinjury and a change in their athletic identity.

While these results don’t explain the differences in ACL injury between females and males, they could indicate the need for a more gender-specific, psychologically focused rehabilitation process in the return to sport process. Perhaps, creating an environment where emotional expression and sports psychology take a more significant and gender-specific role in the recovery process post ACL reconstruction will help both sexes, especially females, return more successfully to their sport.

Photo from racing days:

The Internet as a Source of Medical Information

Connor Crutchfield, BS and Elizabeth Matzkin, MD

Have you ever left a doctor's appointment feeling confused? The good news is, you're not alone. The truth is, medical information can be quite confusing, which is why the American Medical Association (AMA) recommends medical texts used for patient education be written at a 6th grade reading level or lower.14-15 The bad news, as we can all appreciate, is that this is not always what happens.16 As a result, many patients utilize resources beyond the clinical setting to learn about their medical diagnoses and treatment options. Today, the most widely used resource is the Internet. In fact, one national study found that 8 in 10 Internet users search for medical information online.7 Another analysis from 2012 found that 59% of all US adults had searched the internet for medical information within the previous year alone and that 35% of all U.S. adults attempted to make a medical diagnosis or treatment decision using information obtained on the Internet. While we believe this is a positive trend reflecting patients' desire to take more of a role in their medical treatment, there is a growing concern among physicians about the reliability, accuracy, and comprehensibility of the non-peer reviewed medical information available on the Internet.11 In the orthopedic world, a number of studies are now being published to address this very concern. Unfortunately, much of these works have found that even when online information is deemed accurate, the knowledge required to understand it is often too advanced.10 This may explain another new trend we are seeing in which people are now turning to videos as a source of medical information.

While videos online may be easier to digest because of the live demonstrations, visual descriptions, and animations they incorporate, they aren't free of inaccuracies either. In fact, a recent systematic review assessing the accuracy of medical information on YouTube, the largest online video platform in the world, found that an upwards of 20 to 30% of all 2,164 videos analyzed contained misleading information.9,12 Other investigations of YouTube content on hip, elbow, foot, shoulder, and knee surgery found similar results in that videos contained either inaccurate or incomplete medical information.1-6,8,13,15 In other words, YouTube videos are not always the best source of information either.

That is not to say that the Internet is a lost cause, though! Luckily, some online sources are still very high quality. Our advice: always seek out the most reputable ones and check the date on which the information was published – the more recent the better. Good places to start include physician websites, official government sites ending in ".gov" or ".org," and content sponsored by known medical institutions such as Mass General Brigham, Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, Johns Hopkins, etc. These associations ensure the information has been vetted by multiple known entities and is reliable. Finally, to guarantee the most medically accurate information, it is usually better if it’s produced by a physician or their office, like the contents of this blog for example! While sources like the news and other medical professionals are well-intentioned and can be helpful for the basics, current evidence indicates that the information they offer is not always 100% accurate or complete. Similarly, when looking into information about a surgery, we recommend seeking content produced by a surgeon that performs that procedure, since they are topic experts in their fields. Finally, if all else fails and you’re not sure where to turn or what to trust, always feel free to reach out to your own doctor for help or bring the information that you’ve found in to your next appointment! After all, that’s what we’re here for.

If you are specifically looking for more information regarding orthopaedic/musculoskeletal injuries or treatments– we recommend Orthoinfo which is developed and reviewed by the experts at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons - https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/

References:

- Ahuja K, Aggarwal P, Sareen JR, Mohindru S, Kandwal P. Comprehensiveness and Reliability of YouTube as an Information Portal for Lumbar Spinal Fusion: A Systematic Review of Video Content. Int J Spine Surg. 2021;15(1):179-185.

- Akpolat AO, Kurdal DP. Is quality of YouTube content on Bankart lesion and its surgical treatment adequate? J Orthop Surg Res. 2020;15(1):78.

- Celik H, Polat O, Ozcan C, et al. Assessment of the Quality and Reliability of the Information on Rotator Cuff Repair on YouTube. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2020;106(1):31-34.

- Cassidy JT, Fitzgerald E, Cassidy ES, et al. YouTube provides poor information regarding anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(3):840-845.

- Crutchfield CR, Frank JS, Anderson MJ, Trofa DP, Lynch TS. A Systematic Assessment of YouTube Content on Femoroacetabular Impingement: An Updated Review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(6):23259671211016340.

- Etzel CM, Bokshan SL, Forster TA, Owens BD. A quality assessment of YouTube content on shoulder instability. Phys Sportsmed. 2021:1-6.

- Fox NJ, Ward KJ, O'Rourke AJ. The 'expert patient': empowerment or medical dominance? The case of weight loss, pharmaceutical drugs and the Internet. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(6):1299-1309.

- MacLeod MG, Hoppe DJ, Simunovic N, et al. YouTube as an information source for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of video content. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(1):136-142.

- Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, Gramopadhye AK. Healthcare information on YouTube: A systematic review. Health Informatics J. 2015;21(3):173-194.

- Mehta MP, Swindell HW, Westermann RW, Rosneck JT, Lynch TS. Assessing the Readability of Online Information About Hip Arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(7):2142-2149.

- Murray E, Lo B, Pollack L, et al. The impact of health information on the Internet on health care and the physician-patient relationship: national U.S. survey among 1.050 U.S. physicians. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5(3):e17.

- Singh AG, Singh S, Singh PP. YouTube for information on rheumatoid arthritis--a wakeup call? J Rheumatol. 2012;39(5):899-903.

- Uzun M, Cingoz T, Duran ME, Varol A, Celik H. The videos on YouTube(R) related to hallux valgus surgery have insufficient information. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021.

- Wiess BD. Health Literacy and Patient Safety: Help Patients Understand. Manual for Clinicians. 2nd ed. American Medical Association Foundation; 2007.

- Wong M, Desai B, Bautista M, et al. YouTube is a poor source of patient information for knee arthroplasty and knee osteoarthritis. Arthroplast Today. 2019;5(1):78-82.

- Yi PH, Ganta A, Hussein KI, Frank RM, Jawa A. Readability of arthroscopy-related patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Arthroscopy Association of North America Web sites. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(6):1108-1112.

Why Thrower's Shouldn't Skip Leg Day

Connor Crutchfield, BA and Elizabeth Matzkin, MD

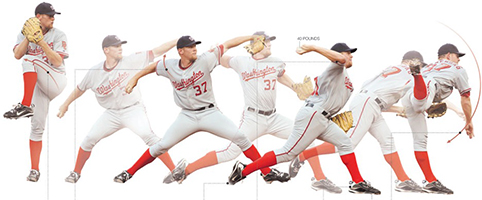

What do sports like football, baseball, softball, and track and field have in common? They all involve throwing athletes. What's more, each sport prizes peak throwing velocities and consistency so much so that there is now a rising trend of earlier sport specialization among younger athletes hoping to reach the next level. This shift toward earlier specialization, however, is associated with athlete burnout and fatigue and is accompanied by a corresponding rise in injuries. The good news is that these athletes can achieve both – better performance and injury prevention – with the proper conditioning.

Now, while it may be intuitive to think that bulking up in the arms, shoulders, and chest would lead to faster pitches or longer throws, that is not what we are talking about. The reality is that most of your throwing power is derived from the core and legs – much larger and more powerful muscle groups. Unfortunately, in focusing on the upper body, overhead athletes often neglect these muscles when training for their throwing sport, especially if the athlete or coach does not mix in some cross-training. Let's use the baseball pitch as an example; it is comprised of 6 phases: wind-up, stride, arm cocking, arm acceleration, arm deceleration, and follow through. The most dynamic movements of which occur from the stride phase through the acceleration phase. Here, the throwing arm and stride leg can reach their maximum anatomic rotations, though injury can occur at any time throughout the movement and become a major obstacle to athletes' staying healthy and in the game. Importantly, when there is insufficiency or limited range of motion (ROM) in the lower extremities, the rest of the kinetic chain is thrown off (pun intended) and the structures in the upper extremities often try to compensate. This can expose throwing athletes to shoulder and elbow injuries like tendonitis, muscle strains, and ligament and labral tears. In other words, it's an easy way to suddenly find oneself on the sidelines.

For this reason, it is vital for throwing athletes to give proper attention to strengthening their legs, glutes, and core; maintaining good ROM; and focusing on proper biomechanics when throwing. Not only can this stave off injury by maintaining efficient energy transfer, but strong legs and a solid core will also boost throwing power. Even activities like golf, lacrosse, hockey, and batting benefit since they require full-body twisting movements driven by the legs, up through the hips, and into the upper extremities.

Take home message: if you want to improve your game, don't skip leg day.

Here are ten exercises that can help take your throwing up a notch:

- Bulgarian split-squat with or without weight

- Side lunges with or without weight

- Curtsy lunges with or without weight

- Side leg (abductor) raises

- Hex Bar deadlift

- Yoga

- Front plank and variations

- Side plank and variations

- Superman hold

- Bird dog hold

Study Finds LGBTQ Health Knowledge Deficit Among Orthopaedic Surgeons

Aliya G. Feroe, MPH

Twitter Handle: @AliyaGFeroe

Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

The estimated proportion of self-identified lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals in the U.S. continues to grow—most recently reported at 7.1%—as acceptance and legislative protections increase around the country. However, we know that health and healthcare disparities persist across LGBTQ communities.

A recent study of the attitudes, knowledge, and practices of pediatric orthopaedic healthcare professionals at Boston Children’s Hospital (Boston, MA) and Nationwide Children’s Hospital (Columbus, OH) showed varying degrees of confidence and basic knowledge of the unique LGBTQ healthcare needs and disparities. However, clinicians expressed considerable interest in focused training and increased use of medical technologies (e.g., clinic intake forms, electronic medical record system) to improve their ability to provide compassionate and informed care to LGBTQ patients.

The following are just a few simple, evidence-based areas on which every clinician can improve today:

- Pronouns (e.g., he/him/his, she/her/hers, they/them/theirs): Learn what pronouns each patient uses and gain comfort saying them. While one option is to ask patients directly during a clinic visit, an alternative is to include this as an optional standardized question on the intake form. While referring to non-binary and transgender patients by their correct pronouns is important, this small action also reassures other sexual and gender minorities that their clinician respects diverse identities.

- LGBTQ-welcoming signage/symbols: Display and don public symbols of an LGBTQ-welcoming clinical/surgical environment. Small actions, like placing a rainbow sticker on one’s hospital badge, hanging rainbow flags or posters of non-traditional family structures (e.g., a child with two fathers), and designating all-gender bathrooms, shows that LGBTQ identities are recognized and valued at that institution.

- Institutional/national LGBTQ health education: Attend trainings to acquire basic communication skills and knowledge regarding LGBTQ individuals. In addition to many general healthcare trainings on LGBTQ health terminology and care, various national orthopaedic associations, including AAOS, RJOS, and POSNA, are producing training materials on the orthopaedic care of LGBTQ patients. Pride Ortho, a group focused on amplifying the voices found at the intersection of LGBTQ health and orthopaedics, is a great resource to keep up with the ever evolving literature.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of action items, but it is a place to start as we work to improve our care of LGBTQ patients.

From Student-Athlete to Medical Student-Athlete

Angela Mercurio

Transitions are hard for many reasons, particularly balancing the important parts of your identity with new roles and responsibilities. For me, transitioning from being a D1 Track and Field athlete to a medical student was a unique challenge.

Balance

Medical school requires taking more responsibility for your education than in previous studies. Still, who you are as a person needs to remain a priority. Being an athlete and pushing my body to its limits has always been part of my identity and I couldn'terase something crucial to my mental health and self-worth. I had to find balance between who I am and my new role as a medical student.

Expectations

I couldn't expect the same level of physicality out of myself as I did in college. Daily workouts used to involve the training room, track,weight room, and continuously exerting myself to the max. That is not possible in medical school (for me!), and I had to be satisfied with that. It wasn't helpful to finish a workout and feel guilty because it wasn't as hard of a workout as my body was once capable of. I had to understand my energy and time limitations, and instead be proud of myself for doing what I needed to take care of myself.

Changes

What does this look like for me? Since retiring from my sport, I've added a regular yoga practice. Yoga combines the rigorous physical aspect of exercise with flexibility, focus, balance, and meditation. Also, I aim for at least 3 days a week of exercise that mimics what I used to do in college (weightlifting, core, sprints, plyometrics), keeping in mind my new expectations for myself.These training sessions are not as long or as challenging as they were in college, but I try to push myself to be better each time. Lastly, I learned to enjoy activities that I didn't used to consider as "exercise" – like walking everywhere or biking to get around. These are great ways to get our bodies moving and feel active, and at the end of the day, that is what's most important!

Instagram/Twitter/Facebook Handles: @thatgurlangie

Institution (Name/Website): Harvard Medical School

It's Lyme Time: Lyme Disease Can Present As A Swollen Knee

Abigail Smith and Elizabeth Matzkin, MD

As the summer season begins, so does tick season. Ticks are miniscule arachnids that are found in most areas of the US. These creatures drink the blood of mammals, including humans. A tick bite may seem insignificant and small, but infected ticks risk transmitting Lyme disease to your body. Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne illness in the US.

Symptoms of Lyme disease are different depending on how early the disease is identified. In stage I, patients may have headaches, fever, and a rash known as erythema migrans. Stage II includes pain in joints, migraines, Bell palsy (muscle weakness of the face), meningitis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord membranes) and fatigue. Stage III happens when the tick bite is never identified, and the Lyme disease is left untreated.

Lyme disease can often present as a painless swollen joint, most commonly as a swollen knee. A swollen knee without any injury or traumatic event could be the first sign of Lyme disease and may warrant testing.

How To Identify A Tick Bite

- Usually on the lower extremities

- Tick attached to skin

- Red spot near bite

- Bulls eyes pattern around bite

- Soreness

- Red rash

This early found tick bite exhibits red spots, bulls eye pattern, and a red rash.

Lyme disease should be taken seriously considering that if left untreated it causes serious musculoskeletal damage. Dr. Elizabeth Matzkin states that "Lyme disease is a problem but can be corrected if caught and diagnosed in a timely fashion". Lyme disease is a common but preventable disease with the right education and awareness.

Snowboard Mountain Prep: Injury Prevention

Catherine A. Logan, MD, MBA, MSPT

Orthopaedic Surgeon, Sports Medicine

Colorado Sports Medicine & Orthopaedics

Snowboarding has been one of the fastest growing and most popular sports of the winter season. The sport combines power, velocity, and technique, making it appealing for both recreational and competitive riders. Snowboarding injury patterns of vary based on skill level; while novice riders experience upper extremity injuries more frequently, elite riders experience a higher rate of lower extremity injury.

New riders more commonly sustain wrist sprains, fractures, lacerations, and contusions. Preventative measures, such as using wrist guards and a helmet, have proven to be effective. Additionally, upon falling, riders should try to hold their hands in a fist position to avoid a wrist fracture.

In more elite riders, the lower extremity, particularly the knee, is more at risk for injury. The anterior cruciate and medial collateral ligaments have a higher incidence of injury secondary to more experienced riders are landing from larger amplitude jumps, riding at increased speeds, and enduring higher impact forces.

Injury Prevention

Injuries may be multi-factorial and may be due to lack of physical fitness, inadequate skill, poor conditions, collisions or improper equipment. Below are some tips on how to optimize physical fitness to prevent the more common injuries.

The average rider should also implement multi-planar, full body movements into their conditioning regimen. Basic exercises, such as a squat, act as a foundation for later progressions including ball tosses and unstable surfaces, for example.

With regard to flexibility, riders should incorporate a regular sequence of yoga inspired movements and holds including hip openers, thoracic spine rotations, and shoulder mobility.

Bridge Progression (Repeat 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions)

- Basic bridge: begin lying supine with arms relaxed at the side with knees bent and feet planted hip width apart. Draw the belly button down toward the spine, tighten the abdominals, then lift the torso toward the sky. Maintain a straight line from the shoulders to the knees, hold 5 seconds, then lower to the starting position.

- Unstable bridge: place the feet on a foam pad or other unstable surface.

- Ball bridge: begin lying supine with arms relaxed at the side with knees straight and heels on a balance call. Draw the belly button down toward the spine, tighten the abdominals, then lift the torso toward the sky. Maintain a straight line from the shoulders to the ankles, hold 5 seconds, then lower to the starting position.

Squat Progression (Repeat 3 sets of 10-12 repetitions)

- Basic squat: begin with feet hip width apart and lower down until the knees are bent to 90 degrees while maintaining an upright torso. Add dumbbells as appropriate.

- Ball toss squat: add a weighted ball toss; return the toss as you rise out of the squat position and while you lower down (different forces will be experienced).

- Balance Board hold: begin with feet hip width apart and maintain a slight flex in the knees with an upright torso.

- Balance Board squat: add a squat while balancing on the board.

Lateral Squats Progression (Repeat 3 sets of 10-12 repetitions, alternate sides)

- Basic lateral squat: begin with feet hip width apart, step either leg out to the side with toes pointing forward, then lower down until the knees are bent to 90 degrees. Maintain an upright torso and add dumbbells as appropriate.

- Ankle resistance band lateral squat: place resistance band around the ankles and perform as above.

Plank Progression (Repeat 3 sets of 20 second holds or 10-12 repetitions)

- Basic plank: begin in the push-up position with shoulders relaxed and the scapula drawn back and down; hold for 20 seconds, rest and repeat.

- Plank on Balance Board: perform as above with the palms placed firmly under the shoulders on the Balance Board; hold for 20 seconds, rest and repeat.

- Push-up on Balance Board: lower the chest toward the board while maintain a straight torso; repeat for 1-12 repetitions, rest and repeat.

- Mountain climbers on Balance Board: maintain a straight line from the shoulders to the heels while alternating controlled knees toward the chest; repeat for 10-12 repetitions, rest and repeat.

*Balance Boards can be replaced by a BOSU or another similar tool.